|

Enhancement of the Quarter: ICE & PACE Value Reports

As always, we at The Phia Group are constantly looking for ways to enhance our service offerings. We have recently enhanced our reporting in certain ways – and our confidence in our services lends itself to full transparency, which we are eager to share with our clients through these reports and others.

Phia Unwrapped Value Report

Users of the Phia Unwrapped service already enjoy unprecedented savings, and we’ve made the reporting even better with the Value Report. This is useful as a sales and informational tool for new or existing groups. It can help showcase differences between a group’s prior wrap network usage and Phia Unwrapped – including providing de-identified information regarding claims volume and savings generated. Reports like this one are designed to help TPAs, brokers, and groups make informed decisions regarding their business processes.

PACE Value Report

Intended for users of The Phia Group’s Plan Appointed Claim Evaluator (PACE) service, this report goes into detail regarding the number of appeals handled, appeal denial reasons, IRO utilization, a numerical summary of appeal outcomes, and more. This report is designed to demonstrate the value of the PACE service, as well as to give the user an idea of what might be the primary issues with its appeals decisions. For instance, if the report revealed that a large number of first-level appeals were overturned by the PACE service, it could spur important process changes.

Service Focus of the Quarter: Phia Unwrapped and No Surprises Act Support

Phia Unwrapped

Wrap, extender, and other leased networks offer small discounts and audit restrictions, affording providers nearly unlimited billing rights. With Phia Unwrapped, The Phia Group replaces wrap network access and modifies non-network payment methodologies, securing payable amounts that are unbeatably low based upon fair market parameters.

Phia Unwrapped places no minimum threshold on claims to be repriced or potential balance billing to be negotiated. Additionally, The Phia Group attempts to secure sign-off, ensuring providers will accept the plan’s payment as payment in full – and if there’s pushback or balance-billing, our Provider Relations team is ready to handle it.

Phia Unwrapped implementation entails setting up an EDI feed with the claims administrator, so claims are flagged, transferred, and repriced automatically. Phia Unwrapped is billed based on a percentage of actual savings, leading to fair rates and no high costs for unprecedented savings.

Out-of-network claims run through The Phia Group’s Unwrapped program yielded an average savings of 74% off billed charges (three times the average wrap discount). On average, The Phia Group sees roughly 2% of claims result in some form of balance-billing; these results are similar throughout many different plan types and geographies, proving that this program and these results can be replicated nationwide.

No Surprises Act Support

Phia’s new No Surprises Act (NSA) support services entail non-network claim pricing, “open negotiation” support, and Independent Dispute Resolution (IDR) defense. Although every TPA potentially has a different set of needs related to the No Surprises Act, Phia can be engaged to perform functions such as checking NSA-related communications to verify the NSA’s applicability and doing a deadline review to ensure that the NSA’s timeframes are being adhered to.

We are also well-equipped with the necessary benchmarking data, domain knowledge, and experience to negotiate claims with medical providers. In addition, if a claim becomes subject to Independent Dispute Resolution, our support services are available to vet and challenge an IDR entity if necessary, as well as review or draft the plan’s offer of payment. Our NSA support services provide the backbone of post-payment NSA compliance, with a particular focus on cost-containment.

Please contact sales@phiagroup.com for more information on Phia Unwrapped or No Surprises Act support!

Success Story of the Quarter: Improving Employee Presentation Skills

As many of our readers have experienced first-hand, The Phia Group’s employees are frequent speakers at conferences and symposiums hosted by TPAs, brokers, captives, stop-loss carriers, and other industry associations, as well as presenters on webinars for both Phia and our clients, podcasts, TPA and broker meetings with groups, and more.

In an effort to help ensure the best experiences for Phia’s valued clientele, Adam Russo (Phia’s CEO) and Ron Peck (Phia’s Chief Legal Officer) – as Phia’s self-proclaimed (yet undisputed) two best public speakers – recently embarked on a large-scale project to help improve presentation skills across Phia’s employees. By having Phia’s key speakers present to them, Adam and Ron scrutinized and critiqued each presentation and gave constructive feedback.

The self-funding industry and its many exciting presentation opportunities are starting to get back to normal, and Phia is excited to get its speakers and presenters back to traveling all over the country for some face-to-face presenting. It’s an exciting time for self-funding and for all those involved in the industry, and it’s a perfect time for Adam and Ron to take steps to improve each presenters’ skills, which will benefit Phia’s clients!

If you need a presenter at a conference, a sales meeting with a group, a webinar for your clients, or anything in between, please keep Phia in mind. Our attorneys and consultants are now even more prepared than ever to present an entertaining, informative, and creative take on any topic you need.

Please contact us at sales@phiagroup.com for all your presentation-related needs.

Phia Case Study: Vendor Contracts & Fiduciary Duties

A TPA client of Phia’s Independent Consultation and Evaluation (ICE) service asked our team to review a proposed agreement between a vendor and one of the TPA’s employer groups. This review was performed at no additional cost to the TPA since it fell under the ICE service (so having the review performed was a bit of a no-brainer).

As we reviewed the agreement, we noticed that it contained language whereby the vendor simultaneously claimed authority to make certain claim and appeal determinations and disclaimed all fiduciary duties. The Phia attorney performing the review inserted some commentary to note the discrepancy and also mentioned it specifically to the TPA as an item for discussion. The employer brought the concern to the vendor to try to get clarity, and the vendor asserted that even though it would make claims determinations, it was not going to be doing so as a fiduciary. From there, Phia explained that that is not possible to perform a fiduciary act but avoid assuming the requisite fiduciary duties for that act.

Armed with this additional clarity, the employer was able to discuss the language with the vendor. As it turns out, the vendor misunderstood the nature of fiduciary duties, and Phia’s feedback helped the employer and vendor better understand their respective legal and contractual obligations and reform the contract to be more accurate. This eliminated potential ambiguity regarding fiduciary liability. It also eased the TPA’s worries that its client, the employer, would get stuck with fiduciary duties for a claim determination that someone else made! .

Fiduciary Burden of the Quarter: Responding to Appeals

ERISA and analogous state law require that provider appeals be responded to. It’s usually a core TPA function, and some TPAs have standard appeal forms that must be filled out in order for the TPA to accept a given piece of provider correspondence as a valid appeal. When there is no “standard” form to fill out to file an appeal, however, appeals may come in all shapes and sizes, and it’s not always so simple to tell what actually constitutes an appeal.

For example, we have seen many letters written by providers that express their dissatisfaction with the way a given health plan handled a claim. Those letters contain all sorts of statements, ranging from (and we’re quoting from real letters here) “this company has [expletive deleted] benefits” to “I demand you compensate me fully,” and everything in between. Some constitute appeals, while others do not. The first example, which we don’t want to offend anyone by reproducing in its original form, is perhaps not an appeal since it didn’t ask for any additional benefits or make any statements, instead suggesting that the plan erred. The fact is, whether a given health plan has [expletive deleted] benefits is a matter of interpretation, but it’s not an actionable request. To contrast, a demand for additional compensation – with or without expletives – is much more likely to constitute an appeal, and we generally believe that it and similar straightforward requests should be treated as one.

When in doubt, our advice is to treat any letter as an appeal. If the appeals have been exhausted, then it may just make a response simpler – but if appeals have not been exhausted, many TPAs see no harm in responding to a general insult of plan benefits and reiterating why those benefits have been paid. If the provider comes back and says, “hang on, that wasn’t meant to be an appeal!” then the response is out there anyway, and it’s all on the record as a good-faith response to a pointless letter. We view it as a win-win.

One thing is certain: if a provider files what a court later deems an appeal and the plan or its designee has not responded to that appeal, that can cause some administrative headaches.

If you need help figuring out whether something is an appeal or the best way to respond to a letter, please don’t hesitate to contact us at PGCReferral@phiagroup.com or your designated Independent Consultation and Evaluation (ICE) mailbox. (For clients of our Independent Consultation and Evaluation service, our guidance is included at no additional cost!)

Webinars:

• On March 22, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “Recognizing Risks, Reaping Rewards… Industry Responses to Costly Threats, and How Plans Must Prepare,” where we discussed costly medical procedures, devices, and specialty drugs

• On February 15, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “The Compliance Landscape for 2022,” where we reveal how you can best prepare a compliance strategy to keep up with new legal developments in ERISA law and with COVID-19.

• On January 25, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “Tune in to Win – Are You Ready for 2022,” where we addressed the issues and trends most in need of your attention, from ongoing litigation to political and regulatory developments to procedural best practices.

Be sure to check out all of our past webinars!

Podcasts:

Empowering Plans

• On March 22, 2022 The Phia Group presented, “A Balancing Act of Reduction Requests and Plan’s Fiduciary Duties,” where our hosts, Chris Aguiar and Cindy Merrell, discuss the balancing act of health plan members’ reduction requests and plans’ fiduciary duties.

• On March 4, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “Healthcare Policy in the State of the Union Address,” where our hosts, Brady Bizarro and Andrew Silverio, break down the important healthcare policy items the President discussed, and just as importantly, which ones he did not.

• On February 18, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “Single Scoops Only (No Double Dipping): COVID OTC Testing,” where our hosts, Kelly Dempsey and Kevin Brady, discuss over-the-counter COVID testing and the complications surrounding up-front payment by participants with account-based plans (HSA, FSA, HRA).

• On February 3, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “The Comparative Analysis: A Year in the Life,” where our hosts, Jon Jablon and Nick Bonds, discuss some of what they’ve learned from a year’s worth of analyzing NQTLs, some practical considerations for health plans, and their takeaways from the recently-published report on MHPAEA compliance from the DOL, HHS, and Treasury.

• On January 20, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “What is Required for Plans for OTC COVID-19 Testing Coverage?,” where our hosts, Jen McCormick and Katie MacLeod, discuss the controversial new OTC COVID-19 Testing coverage requirement that went into effect on January 15, 2022 for plans – how it interacts with other COVID-19 coverage requirements, what plans need to cover and available safe harbors, and how plans can be prepared for compliance.

• On January 6, 2022, The Phia Group presented, “Challenges and Opportunities with Value-Based Care for 2022,” where our hosts, Ron E. Peck, and Micah Iberosi-Parnell, talk value-based care, what it is, where it’s at right now, and where it’s headed.

Be sure to check out all of our latest podcasts!

On apple podcasts.

Back to top ^

Phia Fit to Print:

• BenefitsPro – Top health care issues to monitor for 2022 and beyond – March 21 2022

• Self-Insurers Publishing Corp. – Make Mental Health Parity A Priority For Your Plan – March 4, 2022

• BenefitsPro – Buyer beware: Using account-based plans to pay for OTC COVID tests – February 23, 2022

• Self-Insurers Publishing Corp. – The Cold War Over Health Prices: The value-based care gap and steps for employers to maximize plan value while reducing expenses – February 4, 2022

• BenefitsPro – New year, new COVID strain, new tests – January 21, 2022

Back to top ^

From the Blogoshpere:

• Mental Health Parity: The Hits Just Keep on Coming. For most of the industry, the acronym “NQTL” has become a bit of a four-letter word.

• Being a Prudent Plan Fiduciary Has Gotten Harder. Being a Plan fiduciary carries a lot of responsibility and potential risk for liability – even more so now thanks to a recent retirement fund ERISA case.

• Don’t Forget About Third-Party Liability When Dealing with COVID-19 Claims. When dealing with COVID-19 claims, payers shouldn’t disregard the possibility of third-party liability.

• The DOL wants to Reduce Stigma and Raise Awareness: Why Your Plan Needs to Be Concerned about Mental Health Parity. If your NQTL Comparative Analysis is requested by the DOL, you need to be prepared.

• Reasons for the Value-Based Care Gap Between Public Payers and Employer Groups. The long-term struggle over the price of health care services between providers and payers is a tale as old as time.

To stay up to date on other industry news, please visit our blog.

Back to top ^

The Phia Group’s 2022 Charity

At The Phia Group, we value our community and everyone in it. As we grow and shape our company, we hope to do the same for the people around us.

The Phia Group’s 2022 charity is the Boys & Girls Club of Metro South.

The mission of The Boys & Girls Club is to nurture strong minds, healthy bodies, and community spirit through youth-driven quality programming in a safe and fun environment.

The Boys & Girls Club of Metro South (BGCMS) was founded in 1990 to create a positive place for the youth of Brockton, Massachusetts. It immediately met a need in the community; in the first year alone, 500 youths, ages 8 to 18, signed up as club members. In the 30-plus years since then, the club has expanded its scope exponentially by offering a mix of Boys & Girls Clubs of America (BGCA) nationally developed programs and activities unique to this club.

Since their founding, more than 20,000 youths have been welcomed through their doors. Currently, they serve more than 1,000 boys and girls ages 5-18 annually through the academic year and summertime programming.

Back to top ^

Get to Know Our Employee of the Quarter: Joanna Wilmot

To be designated as an Employee of the Quarter is an achievement that is reserved for Phia employees who truly go above and beyond their day-to-day responsibilities. This person must not only transcend their established job expectations but also demonstrate with fervency a dedication to The Phia Group and its employees that is so unparalleled that it cannot go without recognition.

The Phia Explore team has made the unanimous decision, without hesitation, that there is no one more deserving than our very own Joanna WIlmot, The Phia Group’s 2022 Q1 Employee of the Quarter!

Here is what one person had to say about Joanna: “Joanna Wilmot has gone way above and beyond to help a client defend themselves and their client in an expensive lawsuit. I’ll spare you the details of the suit, but our client desperately needed Phia’s help compiling data. Joanna was given and completed in just two days, the daunting task of sifting through an estimated 1900 plan documents, document reviews, and PACE appeals histories to look for certain specific plan provisions. In addition to the volume, the identification and analysis of the language were far from simple. I’ll repeat that: 1900 plan documents in two days. Thanks, Joanna, for dropping everything and embracing this assignment to help our client in their time of need. You are awesome.”

Congratulations Joanna, and thank you for your many current and future contributions.

Job Opportunities:

• VP, Business Analytics and Data Services

• Claim Analyst

• Case Investigator

• PGC Project Coordinator

• Plan Drafter

• Accounts Payable Specialist

See the latest job opportunities, here: Our Careers Page

Promotions

• Garrick Hunt has been promoted from Sales Manager to Director of Business Development

• Matthew Painten has been promoted from Marketing Manager to Marketing Director

• Kevin Brady has been promoted from Health Benefit Plan Consulting Attorney II to Director, Plan Document Compliance

• Andrew Silverio has been promoted from Compliance and Oversight Counsel to Compliance and Oversight Counsel, Team Lead

• Amanda DeRosa has been promoted from Team Lead, Recovery Services to Manager, Recovery Services

• Naviana Duterlien has been promoted from Compliance Analyst to Internal Audit Manager

• Jen Costa has been promoted from Director, Recovery Services to Senior Director, Recovery Services

• Brady Bizarro has been promoted from Director, Legal Compliance & Regulatory Affairs to Senior Director, Legal Compliance & Regulatory Affairs

• Maya Tamhankar has been promoted from Director, Project Management Office to Senior Director, Project Management Office

• Nick Murphy has been promoted from Senior Project Manager to Director, Project Manager

• Christine Sands has been promoted from Senior Business Analyst to Manager, Data Integrity and Analytics

New Hires

• Jillian Painten was hired as a Sr. Claims Recovery Specialist

• Matthew Kyle was hired as a Sr. Claims Recovery Specialist

Phia News:

Energage Names The Phia Group a Winner of the 2022 Top Workplaces USA Award

It is with great honor and humility that The Phia Group announces that it has earned a 2022 Top Workplaces USA award, issued by Energage. Energage, an organization that develops solutions to build and brand a vast array of companies, leveraged its 15-year history of surveying more than 20 million employees across 54 markets to award this prize.

Earning this accolade was no small task. Several thousand organizations from across the country were invited to participate, and winners of the Top Workplaces USA were chosen based solely on employee feedback gathered through an employee engagement survey, issued by Energage. These results were then calculated by comparing the survey’s research-based statements, including 15 Culture Drivers that are proven to predict high performance against industry benchmarks.

Celebrating Mardi Gras at Phia

The Diversity and Inclusion Committee wanted to make sure the Phia Family celebrated Mardi Gras in the most traditional way possible, with multiple Mardi Gras king cakes. The Phia family had a great time celebrating, and the cakes were enjoyed by all! To learn more about the history of Mardi Gras, visit this article on the history.

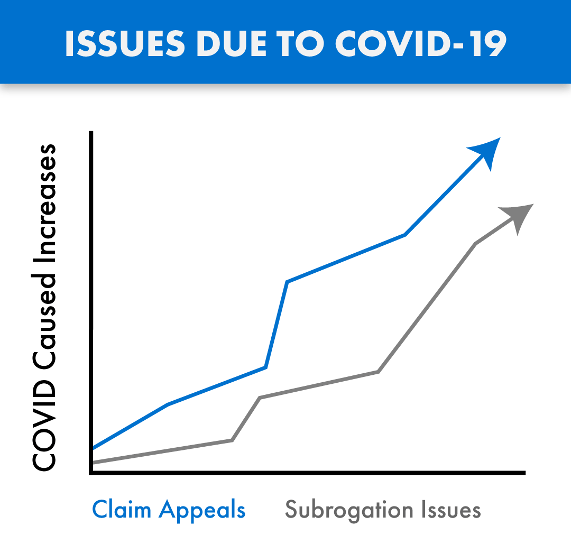

COVID – Appeals, Subrogation, and Stop Loss Issues No One Saw Coming – Help is Here

COVID claims are coming – whether you pay or deny claims tied to COVID, you need The Phia Group.

Claims tied to the treatment of COVID-19 are being submitted for payment and are passing through the claims process in record numbers. Many of these claims are substantial, with these considerable costs impacting our industry in both anticipated and unforeseen ways. As with any influx of new claims, we are also seeing growth in the number of denials and appeals arising from these COVID claims, as well as subrogation issues tied to the disease.

COVID claims are routinely denied and/or paid incorrectly, due in large part to the inadequate time provided to consultants, administrators, and payers, to familiarize themselves with the ever changing rules, and thereby standardize appropriate handling of these claims in accordance with law and their plan documents. As a result, we are also seeing an increase in COVID related claim appeals, with heightened fiduciary liability issues also arising from these claim payment decisions.

The Phia Group’s PACE Service has existed for years and is the only service on the market where expert plan drafters, attorneys, and seasoned appeals professionals help you navigate these and other difficult appeals, thereby avoiding mistakes and costly liability. PACE ensures claim denials are legitimate, enforceable, and defended.

As with claims processing and appeals, COVID has also created a new world for subrogation. When COVID claims are submitted, complex state law may be triggered regarding if and when COVID is “presumed” to be an occupational expense. The Phia Group was the first subrogation provider to build a custom process backed by its in-house legal team with a focus on identifying COVID related claims, determining whether the applicable geographic location and occupation are addressed by a regulation that presumes a link between the occupation and diagnosis, and quickly asserts a right to reimbursement against responsible parties if possible. The Phia Group has been applying this procedure to its existing process since June of 2020. Without an innovative subrogation solution like ours in place, plans not only lose money, but also fail in their obligation to stop-loss; a failure stop-loss carriers are increasingly unwilling to overlook.

The stop-loss world has been handed a unique and difficult scenario. As it relates to claims arising from or tied to COVID-19, carriers are suspending reimbursement and asking questions such as: what is the Plan Participant’s job description; is the Plan Participant a front line worker; what date did they test positive; are they an essential worker; did they file a workers’ compensation claim; and so on. The Phia Group has the expertise to assist in these difficult stop-loss collaborations.

Ensuring appeals are handled correctly, aligning plan documents with stop-loss policies, and fully understanding the bigger picture has never been more important. The Phia Group is uniquely positioned to help in this difficult time. With our unrivaled team and technology ready to help, there is no better partner to assist you now and in the days to come.

Contact Garrick Hunt at ghunt@phiagroup.com or info@phiagroup.com to request more information and set a call to learn how The Phia Group can assist you with these COVID claim issues.

The Phia Group Reaffirms Commitment to Diversity & Inclusion

At The Phia Group, our commitment to fostering, cultivating, and preserving a culture of diversity and inclusion has not wavered from the moment we opened our doors 20 years ago. We realized early on that our human capital is our most valuable asset, and fundamental to our success. The collective sum of individual differences, life experiences, knowledge, inventiveness, innovation, self-expression, unique capabilities, and talent that our employees invest in their work, represents a significant part of not only our culture, but also our company’s reputation and achievements.

We embrace and encourage our employees’ differences, including but not limited to age, color, ethnicity, family or marital status, gender identity or expression, national origin, physical and mental ability or challenges, race, religion, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, veteran status, and other characteristics that make our employees unique.

The Phia Group’s diversity initiatives are applicable to all of our practices and policies, including recruitment and selection, compensation and benefits, professional development and training, promotions, social and recreational programs, and the ongoing development of a work environment built on the premise of diversity equality.

We recognize that the success of our company is a direct reflection of each team member’s drive, creativity, diversity, and willingness to exercise initiative. With this in mind, we always seek to attract and develop candidates who share our passion for the healthcare industry and our commitment to diversity and inclusion.

Back to top ^

|